The history of sexuality in America is not as straightforward as it might seem. Rebecca L. Davis, professor of history at the University of Delaware, joins host Krys Boyd to discuss how gender has determined roles regardless of someone’s sexuality, why the Puritans weren’t so prude, and how our views changed in the 21st Century. Her book is “Fierce Desires: A New History of Sex and Sexuality in America.”

Understanding the history of sexuality in American society

By Madelyn Walton, Think Intern

Conversations surrounding sex and sexuality have always been a part of American history. But looking at a slice of time, from the 1800s to present day, the discussion has widely evolved.

Rebecca L. Davis is a history professor at the University of Delaware, and she joined Krys Boyd to discuss gender dynamics and the evolution of sexuality in America. Her book is “Fierce Desires: A History of Sex and Sexuality in America.”

Davis reveals that sexuality goes beyond gender. In the beginning, an individual’s social status played a significant role in the decision for a man and a woman to pair or be paired with one another.

During American slavery, men would purchase “fancy girls” or sexual companions for their reproductive capacity.

“If you can control someone’s intimate life, you can just exert an extraordinary degree over every aspect of their life,” Davis says. “And in American slavery, the reproductive bodies of enslaved women were extremely valuable and were exploited for that purpose.”

Enslaving women for their sexuality and body control was a system used in America’s collective past. The resistance and struggle for strength is unimaginable today. So much so that we see increased resistance and passion for these issues.

“The title of my book, ‘Fierce Desires’, is really a recognition of how intensely and passionately people fight over issues related to sex and sexuality, but particularly over their ability to make decisions about their own sex and sexuality.”

Davis touches on sexology, or the study of sexuality in the United States. In the early 1900s, sexology became a growing conversation, and it allowed respective genders to find a sense of belonging. The study also helped experts become educated and informed.

“The sexology piece is so important to how we end up with this sort of broader cultural and political stigma surrounding same sex desires and queer identities,” Davis says. “And sexology plays a big part in that.”

In the 21st century, individual choices and freedoms are starting to be recognized. Davis discusses limitations of the past and how far the United States has come.

“One of the themes of the book and that we keep saying over and over again is how passionately people want to be able to make choices,” Davis says. “And sometimes they’re making a choice because that’s who [they are]: ‘That’s my identity.’ And sometimes they’re making that choice because that’s what my community or my religion teaches me.’”

- +

Transcript

Krys Boyd [00:00:00] The way we express our gender, whom we are attracted to, and how we act on that attraction. Sexuality is a big part of our individual identity as Americans in the 21st century. It’s almost hard to get our heads around the time when it all worked very differently when wealthy white men may have been free to choose their own adventures in the bedroom. Pretty much everybody else was shaped by the assumption that their sex determined the role they got to play in society. So how did things change?

Krys Boyd [00:00:27] From Kera in Dallas, this is Think. I’m Krys Boyd. It’s not that we are somehow more sexual than previous generations, although more of us are free to talk about it now, as my guest will explain. One big difference is that where sexual desires and behaviors were once seen as a reflection of moral values. We now think about sexuality as an important component of who a person is. Rebecca L Davis is Professor of History and of Women and Gender Studies at the University of Delaware and author of the book Fierce Desires A New History of Sex and Sexuality in America. Rebecca, welcome to Think.

Rebecca L. Davis [00:01:04] Thank you for having me.

Krys Boyd [00:01:05] So you write that sexuality is something we now see as an essential part of who someone is. This seems so evident that it is honestly difficult to think of another way to frame it. How were things different when sexuality, as we define it today, was not seen as a component of identity?

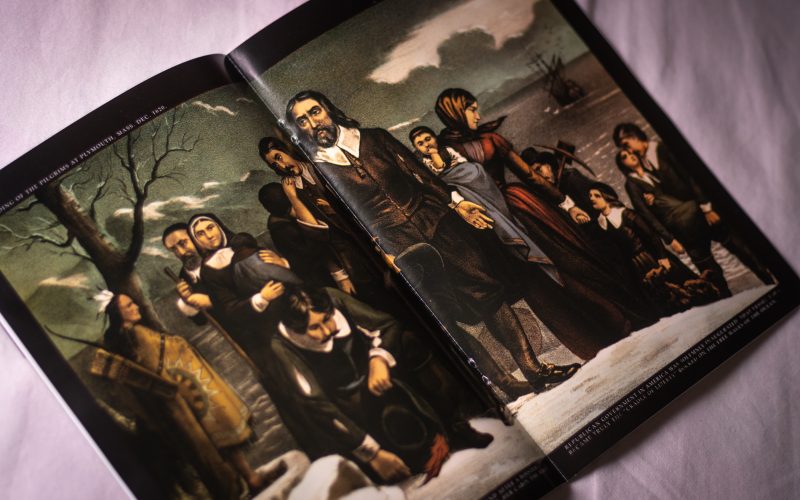

Rebecca L. Davis [00:01:23] Well, it’s so interesting to think back. Let’s say 400 years ago, we had indigenous North Americans, Europeans arriving in very small numbers initially and eventually enslaved Africans arriving. And among the Europeans, there were people who were there to missionaries to convert indigenous people and others who wanted to, you know, get riches from the North American landscape. So people brought with them or already had with them different ideas of how sexuality should manifest in their lives. And what’s so interesting is that across all of these different communities of people, we see an interest in sex and sexuality as part of what knits their communities together. So for indigenous North American communities, sex and sexuality were part of the natural world, something that connected them to ancestors and to the whole cosmic organization of the universe as they understood it. But even for English people coming to New England or to the Chesapeake, they thought about sexual behavior as a reflection of who you were in your community, as a reflection of how faithful you were to your God and to the teachings of your church. And so for these very different groups of people who had very different language and customs and everything, they shared a sense that the way you behaved sexually was a reflection of your people, of your community. And so that it wasn’t necessarily individualistic as we might think about it today.

Krys Boyd [00:03:04] And so gender roles, the social positions afforded to men and women in society or people considered men and women, those trumped whoever an individual was attracted to as a source of identity within a community.

Rebecca L. Davis [00:03:18] Very often it did. I mean, we see in early modern societies and in the 1600s and 1700s into the 1800s. The most important thing was that there be men and women as social roles. There were social functions that different groups of people performed. I mean, these were very hierarchical societies generally. There were husbands and then wives who were supposed to be deferential to husbands. If you’re looking at Anglo-American or Spanish American culture, it was very different for indigenous cultures. But we see that, you know, the way you dressed was a representation of what your status was. So you were not only presenting yourself as your gender, as perhaps you know, as a man, but as a man of a certain status. So it mattered to people what social function you had, what your role was, what you were doing in your society, how you were contributing, who owed you deference, who owed you respect, whom were you supposed to defer to? And so gender was one among many markers of those differences. And when it came to what people did in their intimate lives, it mattered a lot less if it were, for example, two women having, you know, erotically together or even to men as long as it was consensual and it didn’t really bother anyone else, as long as in some ways no one else’s social function or community, you know, stability was affected. You know, it wasn’t aggressively policed. So, for example, in early American, early Anglo America, the local law enforcement was really worried about and communities were really worried and churches were worried about fornication, which they defined as sex with an unmarried woman. So they would you know why? Because, you know, an un a woman was supposed to be virginal until her marriage. So that was a sense of both, you know, for her father, a sense of whether he’d done a good job protecting his daughters and keeping a, you know, respectable family. But also the possibility of a child to an unmarried woman was very socially disruptive. So we see a lot of churches and courts in the 1600 1700s worried about fornication, about what they called bastard, which was an illegitimate child. And we see hardly any sodomy prosecutions. It just what people as long as it wasn’t, for example, a younger man accusing an older or higher status man of attacking him with assault. It didn’t really reach the level of community concern as far as the records we’ve been left with can tell us.

Krys Boyd [00:06:02] So one thing that I learned from your book was that in the colonial era, part of the reason that, you know, people were very anti fornication was that like if indentured servants were having babies, those babies would mean their employer had another mouth to feed. That was a problem.

Rebecca L. Davis [00:06:20] Absolutely. I mean, I was I’m always surprised. And when I go back and read about the 1600s into the 1700s in America, how much of the labor force was comprised of indentured servants? These were folks who came from England or, you know, other parts of Europe who were had their way across the Atlantic paid. And when they arrived, they’d get their food and housing paid in exchange for seven years of work, usually during which they were not supposed to marry unless they had explicit permission from the people they worked for. They weren’t supposed to form their own households. Being the head of the household was one of those gendered status positions, and only men with a higher status were supposed to do that. So you couldn’t be a head of household with dependents if you yourself were supposed to be a dependent in someone else’s household. So, yes, these indentured servants could get in a lot of trouble if they were horsing around, if they were having, you know, girlfriends and boyfriends. Of course, this happened, though, all the time. And that’s why we see so many of these fornication prosecutions. You can’t take young adults and say, you know, you can’t have sex for seven years. Doesn’t that really practical? So but we also see is that, you know, these indentured servants were given opportunities that people who were kidnaped from Africa and brought either to the Caribbean first or right to the to North American shores were never given. You could become free. You could become a free man or free woman after your term of indenture and in split, people enslaved from Africa and their descendants were not given that opportunity to become free automatically. It was a very arduous process if it was available to them at all. But becoming free meant you could then marry. You could become your own head of household or your own, you know, wife to a head of household.

Krys Boyd [00:08:17] And aside from the risk of sexual assault for enslaved people, there were enslavers who tried to control the sexual relationships of the people they kept in bondage.

Rebecca L. Davis [00:08:31] I mean, it is this was one of the hardest things to write about and research for this book and also one of the most shocking. I mean, if you can control somebodies intimate life, you can just exert an extraordinary degree over every aspect of their lives. And on in American slavery, the reproductive bodies of enslaved women were extremely valuable and were exploited for that purpose. And especially after the closing of the wall, the end of the United States participation in the international slave trade after 1808. There’s increasing pressure from enslavers slave traders to increase the population of enslaved people through pregnancies. And so there’s a great deal of coercion involved. There were enslavers who kept track of the menstrual cycles of the women they enslaved. Wow. They yeah, I mean, they wanted to know, were these women having, you know, were having abortions? Were they miscarrying on purpose? If you if if a trader sold, you know, this is this I mean and I just get up it’s horribly upsetting. Right where if if an Enslaver, for example, had purchased a woman on the promise that she was fertile and it turned out she had uterine cancer. There were lawsuits. There were, you know, saying that this was false, these were false good, you know, a false bill of goods. And so you see these networks of sales and disputes and contract, you know, confrontations among enslavers and slave traders over whether or not and women who were enslaved were fertile or could become childbearing while they were enslaved. So this this capacity of enslaved women for the reproductive capacity of women was one of the values placed on enslaved women. And there were other women who were often purchased very young, often around age 14, who were and there was a whole secondary market in the United States in under American slavery and often lighter skinned, very young girls who would be purchased to be sexual companions of the men of the white men who purchased them. And this was often called like these were called fancy girls. There were there was a whole separate terminology around them. And we have firsthand accounts from some women who survived this and then were able to free themselves and then partner with northern abolitionists and write their stories. So we we know a lot about what this process looked like from their perspectives, but there were all kinds of ways in which sex was intrinsic to American slavery.

Krys Boyd [00:11:31] The other thing you write about that is, I mean, it’s hard to even say out loud, but there were enslavers who thought of themselves as please excuse the term breeding the people they kept enslaved like they were making choices about which partnerships would would give them the best baby that they would also enslave. Were there any ways that people were able to push back on this or somehow exert their own will over the kinds of relationships they wanted?

Rebecca L. Davis [00:12:01] People are endlessly creative and resilient. And, you know, the title of my book, Fierce Desires, is really a recognition of how intensely and passionately people fight over issues related to sex and sexuality, but particularly over their ability to make decisions about their own sex and sexuality. And this is absolutely one of those instances. So there are all kinds of instances where women fought back and sometimes were then punished for fighting back to resist abuse. But there were also more anecdotal but plenty of evidence of women, for example, chewing cotton, root, cotton root will make you very, very sick, but Will can make a pregnant woman sick enough that she will miscarry. And so there were women who, you know, who said that they chewed cotton root basically constantly while they were enslaved to not get pregnant. And the sort of implication being that they were at the time being abused by white men and then subsequently after, you know, the Civil War and they had their freedom were childbearing, women were able to have children on their own terms. And I think that we can also look at examples of midwives, African-American midwives who did everything they could to help laboring women, pregnant and laboring women under terrible circumstances. We can see all these tiny acts of resistance, but I think those intimate acts are so crucial to thinking about, you know, where where does strength come from? And also, why are people so and so passionate about issues around gender and sexuality and body control? It’s because it’s been something that has been very important to our our collective past.

Krys Boyd [00:14:02] Rebecca Presumably most of us imagine being married in the colonial era to be not very much fun. But there were. Is it going too far to say pro sex puritans?

Rebecca L. Davis [00:14:14] I know, right? I mean, I think that the Puritans get such a bad rap when it comes to our narratives of sexual repression. And we really owe that more to to 19th century novelists who wrote about, you know, the Puritans as being a bunch of, you know, prudes. But in fact, Puritans who were, you know, this Protestants Act, who came from England and the Netherlands and settled in New England and other parts of North America, they really embraced sexual pleasure within marriage. And the within marriage part was absolutely essential to their understanding of proper sexual relationships. So they were very critical of, you know, fornication and adultery and sodomy, as they called any sex between men. But when it came to sex between a married man and married woman, they thought that was actually part of God’s beauty. And some of this was political. I mean, they were really saying this is what makes a Protestant different from a Catholic. And in Roman Catholicism, the highest level of sort of sexual godliness is to be chaste, is to be celibate. And Puritans were saying no. In fact, the greatest, you know, demonstration of sexual love, the most sacred kind of sexual love, is what happens between a husband and a wife. And so they were very, very pro sex in that way. And they also were kind of excited about what happened when a believer came into sort of a relationship with God and used the language that, you know, the believer was the bride of Christ. And they used that language, whether the believer was male or female. They saw they saw penetration at some mission as fundamentally feminine attributes. So if a male puritan was experiencing beatings sort of felt, but then he did so in his understanding as a bride. And so they were. But again, this is where they weren’t caught up with, you know, defining that as being, you know, is that gay? Is that homosexual? That question would not have made any sense to them. They were thinking about this is an obviously a male bodied person, but he is experiencing a female moment in his sort of divine, ecstatic receiving of God’s love. And so they played around with this language of sexuality, both in their faith and in their celebration of marriage. So, yeah, they they weren’t afraid to talk about sex at all.

Krys Boyd [00:16:59] But in other colonial communities, young women were sometimes allowed, maybe even encouraged to have sleepovers with their boyfriends. Tell us about this.

Rebecca L. Davis [00:17:09] Yeah. So there’s a practice called bundling, and we think it is sort of a northern European import. And one of the ways in which, as you’re saying, parents would give permission for male suitors to spend the night in their daughters beds and that and that obviously opens up all kinds of possibilities. The house where it comes from is that we think this sort of northern European practice that was brought to the to the America to America. I mean, on the one hand, there weren’t many beds, so it was absolutely normal that if a guest came to visit or a family of guests, you would just sort of divvy them up into the existing beds in the house. Only the wealthiest people would have had a guest bed. And even within a household, people slept many people to a bed. It was very cold at night. There was actually a global sort of low temperature era for many decades. In the late 1700s into the early 1800s, it was especially cold around the around the world. But they you know, they didn’t have internal you know, they didn’t have an AC system, so they would climb into bed. Bundling was a special situation where the suitor and the man who was courting the daughter and the daughter would be allowed to sleep in bed. And the bundling. Sometimes it may have been that the daughter would be sort of wrapped up in sheets, or maybe the young man would also be wrapped up in sheets to make it obviously trickier for them to fool around. But it was also a situation in which these young women had a lot of say over how much physical intimacy was going to transpire. These were very small homes for the most part. Walls weren’t very thick. If she had felt at all at risk, like in danger, like this is going faster than she wanted or something. Terrible just happened. If she called out, there were people, her family, you know, just a, you know, a door away, who would be right there. Also, if she did get pregnant, her parents would know exactly which young man was responsible for the pregnancy. And again, you know, premarital pregnancy rates were actually pretty high in the latter part of the 1700s. You know, sort of Revolutionary War era toward the end of the century. And, you know, bundling whether bundling was a cause or a response to those premarital sex, you know, sex rates. I don’t know. But it’s certainly we can certainly see them as part of the same phenomenon. But in this instance, rather than having, you know, a daughter who gets pregnant and then is like a disgrace to the family because she’s going to be an unwed mother, the family could say to the young man, well, you were in our house in our daughter’s bed. We know it’s you. You guys have to get married now. So that afforded the family also a degree of control. I suppose, that if you’re at the point where there are many more young women in your community getting pregnant before getting married, adopting some sort of system that allows you to have some oversight over that perhaps was appealing to certain parents. But there are also really find like diary and entries by young men of the time saying just how much fun they were having with this new pastime of getting into different friends beds, different nights of the week. So it does seem that this went beyond just pre-marital courtship.

Krys Boyd [00:20:35] So people from Europe established themselves on this continent and encountered all these different civilizations that had different ideas about identities and sexual identities. What did Europeans make of indigenous traditions that allowed for a greater range of gender and sexual identities than what they had been familiar with in the old country?

Rebecca L. Davis [00:20:59] Well, and I mean, unfortunately, the response typically was to take greater freedom to, you know, to observe greater freedoms for indigenous women and and interpret them not as freedoms, but as evidence that, for example, these women were sex workers. Right. If if a woman is is not married and is having sex with, you know, different men and, you know, at different times, well, then surely she must be a sex worker and not, as was often the case in some of these indigenous nations. A young woman who was given full autonomy to decide who her sexual partners would be and to have a variety of them before she married. So there is, you know, that kind of assumption that comes into it. And they really also interpreted it as a sign that Native American men were weak, that they didn’t control their women, which was a value among a lot of these Europeans as they were who were arriving in America.

Krys Boyd [00:22:03] So. How did the field of sexology arise as an academic pursuit?

Rebecca L. Davis [00:22:12] So sexology is really a fun topic, I think. I never get tired of learning more about it. It’s a funny word, but it’s basically the science of sex. And you know, the very first attempts to study to come up with a science of sex. We can see in the early 1900s, there were these very brave sex educators who took a lot of risks to publish information about human anatomy, often with the goal of trying to educate women about how, you know, how human reproduction worked, what the various methods of preventing pregnancy might be, and things like that. And that was the first sort of study of sexuality in the U.S. But sexology kind of starts in Europe, where the medical profession and science were more advanced at the time than in the United States in like the 1860s, 1870s. And it’s a hodgepodge of people. It’s social reformers, it’s psychiatrists and analysts. And they are trying to understand what makes certain people desire different kinds of sex. So on the one hand, there are reformers who live in like at the time, and in England, in Germany, there were very strict anti-sodomy laws. And so there were men who were attracted to men who were saying, we’re not we’re not mentally ill and we’re not criminals. We’re just a different kind of sex. And there was a theory of sort of inversion that if you took a male body but you put a female sort of soul within that person, you would end up with a man who desired sex with another man like he was. His his gender to sex relationship was inverted. And, you know, and and this idea was, you know, crafted with the goal of destigmatizing queer sex. And then there were others very influential sexologists in Europe who worked in psychiatric hospitals or who had private practice, who became much more interested in sort of coming up with labels like, we have this and this and this. We have the pederast and the sodomite and the, you know, this person with this fetish and that fetish. And we want to sort of plunk them all down into different diagnostic categories. And then in the end, so these ideas cross the Atlantic and we have sexologists in the United States who by the 1890s and early 1900s are looking at, for example, masculine presenting women or queer people that we might today think of as trans men at the time were viewed as mannish lesbians and might in fact have viewed themselves as mannish lesbians and thought about them as actually now mentally ill, that we need to put these folks into a separate category of mental illness. We need to think about this as a diagnostic category. So there’s a photo I often show my students, and it’s from a 1911 medical text, and it’s just a photograph of two queer women who were a couple. But they were, you know, especially they were specimens of this new thing called the lesbian or sort of the female invert. And so from sexology, you start to see these labels applied to categories of people. But part of what’s so fascinating about sexology is that the patient spoke back to the physicians and the scientists and would say, you know, I think I’m one of these people I read you were writing about in this book. I read your you know, because one thing that’s fascinating as an aside is that queer people have for generations gone to serious medical and scientific texts that weren’t really meant for them, that were really intended for other professionals, that were meant for like other scientists or other physicians, but read them voraciously as one of the few sources of information they could find about people who felt things like they felt. So both with Sexologists in the 1800s and into the well into the 20th century, these sort of serious, rigorous scientific medical texts became very widely read by queer people. So you’d have one of these medical texts out there saying this is what the homosexual is. And gay men would read this and say, Now you didn’t quite get it right. And they would write letters back to the authors of these books and say, you know, I think you were right, this thing you said here, but this other part. No. And let me explain to you why. And to their credit, a lot of these scientists were fascinated. Physicians were fascinated by these responses that they got to their to their books and even modified them over time to try to be less stigmatizing of queer desires. So sexology becomes a sort of conversation among people. Or who see themselves as experts because of their training and their education. And then individuals who speak back to them from their own experiences.

Krys Boyd [00:27:22] Rebecca, if I’m understanding you correctly, before sexology arose as a field of study, there may have been some people who disapproved for whatever reason of same sex attraction, but it wasn’t like stigmatized in quite the same way as as implying that there was something wrong with a person in the same way that it did until like homosexuality was removed from the DSM in the early 70s as a mental health disorder.

Rebecca L. Davis [00:27:52] The medical piece. The sexology piece is so important to how we end up with this sort of broader cultural and political stigma surrounding same sex desires and queer identities. And that’s and sexology plays a big part in that. I also think a key aspect of it is the growth of policing in the United States and the emergence of this idea that it is the business of the federal government and of state and local governments to proactively look for sex crimes or evidence of improper sexual communications, and that that is actually something police should do. You know, in the early 1800s, there weren’t really professional police forces at all. And a lot of other historians have have shown how important slavery and the end of slavery were to the growth of police presence, police forces in American cities. And another and one of the ripple effects of that is with more police. One of the things police start to do is look for evidence of, quote unquote, fights. They start arresting people they describe as vagrants or as degenerates, people who they say were causing new sort of misdemeanor categories of public nuisance. These weren’t really thing. No one was really arrested for those kinds of things in large numbers before. In the 1700s, we do have the arrest of someone who cross-dresser was trans for being for causing a public disturbance. But by the flash forward 100 years to the later 1800s, many cities had passed laws in their cities making cross-dressing a crime. And then police would go out and look for people who they considered to be cross-dressing. Who. And that’s a word that is even uncomfortable to use now, because we would really be talking about trans people who were wearing the clothes that they wanted to wear and that were at, you know, whatever was sort of fashionable for their gender. So those that that becomes a proactive process by local governments, states and even the federal government only at the end of the 1800s and into the early 1900s, such that like you end up with police forces having a dedicated vice squad that you know, is going to decide to patrol parks and public restrooms and the public library and rest stops along, you know, rural highways to go and look for men who are seeking or having sex with other men. They’re going to start using decoys and entrapment and all kinds of sometimes not actually legal strategies to bring men in, to find people, to force them into situations where they have done something that warrants an arrest. So all of that is very novel and sexology is super important to it, but the growth of policing is also really key.

Krys Boyd [00:30:59] So, Rebecca, as you just described, starting in the late 19th century, these, you know, vice squads were around. You had the policing of sexual relationships in a lot of different forms, including polygamy out west with the Mormons under the leadership of Joseph Smith temporarily. People in this country have also always pushed back on government attempts to regulate and tell them what they can do in their private lives. So what was the the confluence of that increased policing of people’s very private, intimate lives and this sense that who you were and who you desired sexually was a part of your identity.

Rebecca L. Davis [00:31:42] In the late 1800s, in the late 19th century. A very pivotal law is passed by Congress called the Comstock Act. It has a official much longer name, but it’s named for Anthony Comstock, who basically wrote the law and presented it to Congress and got his allies to to help him get it passed. And it set incredibly broad parameters for what was obscene and empowered him under a new designation as sort of a postal inspector to go out and search for evidence of violations of this new law and also defined contraception and abortion as forms of obscenity. And so this was different from there had been really fairly weak American anti obscenity laws prior to that, mostly affecting importation. Now, Comstock was saying that any that interstate commerce, the Interstate commerce clause, gave Congress the authority to regulate anything that basically he considered obscene from traveling through the U.S. mail. And and he really went after free speech activists who were some of the most. Compelling and passionate antagonists of this new anti obscenity regime. And free speech activists were often, you know, accused of blasphemy if they were standing up for atheists, but they were also often standing up for sex educators. They were standing up for women who wanted to talk with other women about sexuality. And Comstock went after them ferociously. And there were major free speech and sexual speech activists who were imprisoned at hard labor. He drove several people to commit suicide and was boastful about this. He was proud of the power that he had, and he did really quiet down the public opposition to these control methods because it became apparent that there was a really high cost. But at the same time, there emerged a black market in contraceptives. There was euphemism galore when you wanted to go search for contraceptives or even abortifacients. The Sears and Roebuck catalog carried advertisements for devices that we can look at now and say, Well, that’s a syringe that was maybe used for Duchenne or maybe it was used for abortions. And of course, it could have had multiple uses. There were patents that, you know, people inventors were put in patents for devices that were clearly contraceptive devices, but would call them all kinds of other things in order to get them approved by the patent office. And so this sort of underground network in contraception and abortifacients really thrived. And the other thing is that the crackdown on queer men and to a lesser extent queer women was very gradual. It was actually female sex workers were targeted by the police most vehemently initially 1890s, early 1900s. And it’s only sort of as gay life becomes more visible and more exuberant and celebratory that it becomes more of a target of the police in the 19 tens and 1920s. So people resist, you know, by having lives that they try to continue having despite the police. And they resisted by using euphemism to continue to share information.

Krys Boyd [00:35:16] Did the crisis around HIV and Aids contribute to a kind of coalescence of queer identities as a powerful, determinate determinant of who someone was?

Rebecca L. Davis [00:35:29] That’s a great question. In some ways, yeah. I mean, this is sort of a yes and no answer. So, you know, the first cases of what we now understand as HIV aids were identified in 1981 in the United States, and initially how the disease spread and, you know, which illnesses comprised, it was very much just information like people were still struggling to find information. There were already pretty well-established gay and lesbian organizations by the time and gay and lesbian health clinics, which became major sources of information for straight physicians who were trying to figure out what was going on and for straight researchers. But you also see new coalitions forming of queer people trying to create resources, trying to work together to advocate for themselves and for their loved ones. And in fact, what’s really interesting is, you know, during the 1970s, when gay liberation had really flowered, there were organizations that included queer trans people, men and women, But there were also a lot of lesbians who didn’t feel at home in gay advocacy groups or gay liberation groups because they said, you know, they’re still show it’s still men being chauvinist and not treating women as equals. So there was a bit of division in the advocacy in the community building between lesbians and gay men. With the Aids crisis, a lot of lesbians became caretakers of friends and loved ones and of strangers. And because so much of the response to HIV aids in this country was horribly homophobic, they recognized, as many did, that this sort of broader category of gay or homosexual or queer was something that united them with gay men. So, you know, there’s not necessarily the case that women who have sex with women or men who have sex with men or people having queer sex of any kind would see themselves as having anything in common. Like their their gender expressions are very different. Their political realities are very different. But with something like HIV Aids and the government initially doing absolutely nothing to respond, to help. And in fact, laughing at press conferences when when asked by reporters about what the administration is going to do, this sense that LGBTQ people, this bigger category, had in common this need to help one another, that they were viewed by the people who hated them or feared them as having something in common so that they could build coalitions where they collectively advocated for their rights.

Krys Boyd [00:38:27] Before the era of Roe v Wade, If I understand this correctly, Rebecca, it was mostly the Catholic Church that institutionally opposed abortion rights. How did it happen that many Protestant denominations that hadn’t really weighed in strongly on this before jumped on that as a moral cause rather than simply a legal issue?

Rebecca L. Davis [00:38:46] Today, often the people telling us about this are evangelical Protestants that a lot of that argument is a Catholic theological position about. And soul meant that the soul enters at the moment of conception. And in the late 1960s and early 1970s, several states had already started to liberalize their abortion laws. So beforo V Wade, there were already both more opportunities to get a legal abortion in the United States and more organized opposition to legal abortion, particularly led by Catholics at the time. But with the growth of the feminist movement and the seeming inevitability at the time of the Equal Rights Amendment and things like that, Catholic activists reached out to Protestant activists to say, look, they want to change the family. And the they was feminists, lesbians, gay men, you know, sort of all in one umbrella under one umbrella. And we now, meaning sort of their definition of a Christian, have to build a coalition and to resist that, to fight back against that. So these sort of family values, language, this idea of there being but one form of American family, one vision of the American family, which was the one that they advocated for, that it was really under threat, was something that they could build a coalition with. And sexual conservatism united these otherwise very disparate groups. I mean, if you think about it, in 1960, major, very prominent American Protestants had basically said, John, JFK should not be president because no Catholic can be a president of the United States. And just within like ten years, you have this major coalition among Protestants and Catholics in opposition to feminism, to abortion, to gay rights, to sex education, in public schools.

Krys Boyd [00:40:46] You note, Rebecca, that today we have two seemingly contradictory trends among young people, which is erotic liberation on the one hand, and sexual avoidance on the other hand. How is it possible these things are happening simultaneously?

Rebecca L. Davis [00:41:01] Well, one way to think about it is through the lens of autonomy. So, you know, there’s and one of the things that I talk about toward the end of the book is you’re referring to is that when surveyed teenagers today are having sex at later ages, you know, initiating sex at later ages and having it less often than teenagers of earlier generations, even fairly recent, earlier generations. And yet, at the same time, there’s this trend of polyamory and ethical non-monogamy. And this fewer people are getting married in the United States. So non-marital sex of many varieties is increasingly widespread. There is far more openness about LGBTQ identities and sexual desires. So there are these two things are intention. I actually, though, think we could look at them as two data points from the same trend line, right? That they are both about people feeling empowered to make decisions about what kind of sex they want to have, with whom, how often, under what conditions. And, you know, it’s I don’t know, to step in another another issue here. But we hear sometimes in our political discourse this sort of lamentation about declining birth rates. And I always think to myself. But doesn’t that just mean that more women are able to make decisions about when and how often they get pregnant? Maybe we could celebrate, You know, is it that maybe, you know, there’s just that many more women who, given the choice, choose not to or choose not to not get pregnant as often? So, again, I think that. You know, one of the themes of the book and that we keep saying over and over again is how passionately people want to be able to make choices. And sometimes they’re making a choice because that’s who I am. That’s my identity. And sometimes they’re making that choice because, well, that’s what my community or my religion teaches me.

Krys Boyd [00:43:08] When we speak to individual beliefs, I mean, as individuals, we want what we want. We want to be able to do what we want to do without anybody else weighing in. I mean, cultural norms might be very permissive or they might be very restrictive, but by definition, they’re never going to work for everybody. Will cultural norms, though, always sort of dictate the standards of this country’s sexuality?

Rebecca L. Davis [00:43:32] I mean, that’s such a great question because it gets me thinking about, well, where do these cultural norms come from? And I think that we’re today living through a really fascinating. Sort of. You could, depending upon your point of view, crisis or transformational moment in thinking about gender and how whether or not it’s a very flexible plastic category or whether it’s very fixed and biological. And so that to me, I see that as a cultural moment very much thanks to a younger generation that is teaching all the rest of us how they see gender and the relationship they see between gender and sexuality. So. I think that yeah, I you know, and that’s, of course, very threatening to people who want to say that no, that there is this one standard or one set of behaviors that everyone should live according to. So that is it is tricky to kind of piece apart what is the, you know, sort of chicken and egg experiment between, you know, people’s behaviors and cultural norms. But I always tend to land on the side of we need to give people more credit for shaping the world that they’re in and for interpreting and playing with and experimenting with the norms that they might receive from their broader cultural moment or their elders or their, you know, religious instructors, the science or the medicine that they learned that we take those bits of information and we interpret them and come up with our own response to how that matters or doesn’t matter to our own expression or behavior.

Krys Boyd [00:45:19] Rebecca Al Davis is professor of history and women and Gender studies at the University of Delaware and author of Fierce Desires A New History of Sex and Sexuality in America. Rebecca, thank you for making time to talk today.

Rebecca L. Davis [00:45:32] Well, it’s been my pleasure.

Krys Boyd [00:45:34] Think is distributed by PR X, the public radio exchange. You can find us on Facebook and Instagram and listen to our podcast wherever you get podcasts. In all those cases, just search for KBR. A think our website is think that KLR a morgue. While you’re there, sign up for our free weekly newsletter. Again, I’m Krys Boyd. Thanks for listening. Have a great day.