In a chilling work of new fiction, A.I. takes over all jobs and humans struggle to adjust. Helen Phillips a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award. She joins host Krys Boyd to discuss her novel about a near-future techno-dystopia, where escaping to nature is the only way to heal – and how her characters make difficult decisions to find solace away from looming technology. The novel is called “Hum.”

- +

Transcript

Krys Boyd [00:00:00] By a lot of measures, the 2020s have not been easy. We started the decade with the pandemic, which, combined with our anxieties over climate change, economic inequality and rising prices for pretty much everything. The encroachment of technology into absolutely every aspect of life has reshaped our working lives, our relationships and our cultural norms. Parents are as invested in it’s ever in, trying to do what’s best for their kids. But all this rapid change means they can’t recreate the conditions that worked when they were kids. So all this we know and we’re dealing with it, but how would we manage if, say, a few years from now it all got more intense? From Kera in Dallas, this is Think. I’m Krys Boyd. Helen Phillips new novel is set somewhere in the possibly not too distant future. At a moment when the climate has deteriorated to the point that rather than Disneyland style rides, the most desirable amusement park is just an urban oasis from the heat and filthy air in which kids can sink their feet into real grass, bathe in clean water and experience the minor miracle of picking and eating fruit right off the plant. It is something Phillips protagonist May so desperately wants to give her own children that she undergoes an experimental procedure to literally change her own face. So she is no longer recognizable to facial recognition technology that surrounds everyone all the time. May’s family needs the money she earns just to get by. She herself has lost her job to the A.I. she helped train. But it’s easy to relate to her desire. In fact, maybe her need to just do something amazing with and for her husband and children. What follows in the book is at once a dream and a nightmare come true. Helen Phillips is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers Award. Her new novel is called”Hum.” Helen, welcome to Think.

Helen Phillips [00:01:54] Thank you so much for having me. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Krys Boyd [00:01:56] One really fascinating thing about this story is that you put your character May into a world that is, I mean, unquestionably more bleak than the one we inhabit today, but also quite recognizable to anybody navigating the 2020s. Like all the anxieties we have today, just made real and turned up to 11. Will you describe that world for us?

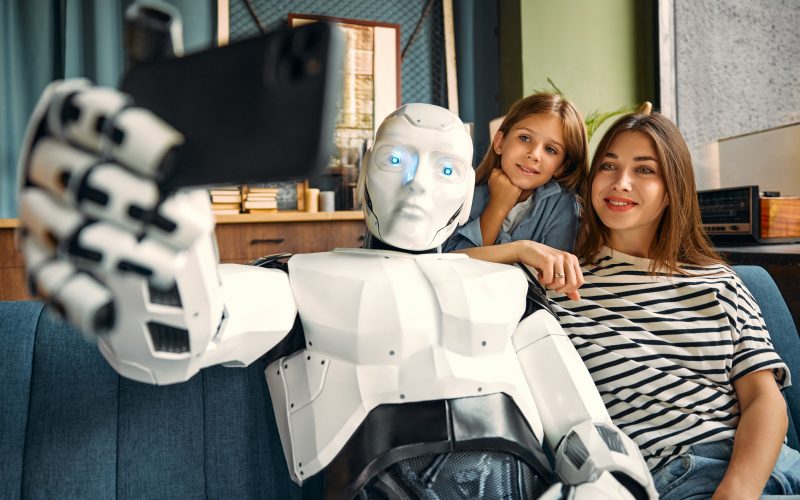

Helen Phillips [00:02:19] Yes, it is a near future, although I would say people have called the book prescient. And I must say I hope it isn’t prescient, but it is. That’s not exactly what I want for it, but it is imagining about five minutes in the future, as one reviewer put it, in a world where humans live alongside superintelligent embodied robots and where climate change has progressed even more. And when I was writing the book, I was very much inspired by my own anxieties as a mother and as a writer about the world that we are creating for ourselves and our children in terms of technology and climate change and surveillance.

Krys Boyd [00:03:06] You include something that is not typical for works of fiction, which is a set of end notes that ties moments in the book to real life events that were happening as you were writing or preparing to write. How do you incorporate research into your fiction?

Helen Phillips [00:03:21] Yes, the book really began as research with the set of anxieties I had. I really wanted to delve deeper into each of those issues and understand them better. And so I began by reading a bunch of books which indeed, as you mentioned, are cited in the end notes. And I find research to be a very important part of the writing process, especially when I’m trying to create an alternate world. I was reading works and books and articles by a lot of people who are thinking really deeply about the future and what it could look like. So simply in terms of worldbuilding, I wanted to do a lot of that research to evoke this near future and a convincing way. Margaret Atwood famously said at one point that everything in A Handmaid’s Tale has some basis in reality. And that idea has always been very interesting to me. And when I was writing Hum, I was thinking about that, that I am creating a reality that is not entirely familiar to readers, but has a lot of basis and seeds in the world that we do now.

Krys Boyd [00:04:23] We should talk about the hums, which are these humanoid robots that have taken over a lot of jobs once performed by human beings. They’re suddenly everywhere and they’re a tool, but also a source of massive disruption. And it made me think about living through the early era of smartphones, which seem to have, you know, gone from being this tool for only really fancy rich people to suddenly being ubiquitous.

Helen Phillips [00:04:49] Yes, homes are complicated. And my hope is that as readers are going through the book, they have a huge range of feelings towards the hums. I hope that they find them frightening. I hope they find them adorable. I hope they find them wise. I hope they find them threatening. I hope they find them sinister. I hope they find them comforting because I feel like that range of feelings is really what I have towards the technologies that surround me and even towards my smartphone. I appreciate that. I can’t really be lost because this phone can help me navigate my city streets. But also is something given up when you can never, ever get lost anymore? So I’m really writing about that gray area of our relationship with our technology and all the different range of feelings that we can have towards these technologies that surround us.

Krys Boyd [00:05:42] Yet listeners who haven’t yet read the book should know the hums are not designed to seem menacing. They are endlessly patient and polite, and they seem programed to like soothe stressed out humans.

Helen Phillips [00:05:56] Yes, indeed. They’re cute. They’re 4’11, so they’re a small, non-threatening height. They don’t look like some of the terrifying robots that you might encounter in science fiction movies or even some of the more terrifying looking robots that have been designed in our real world. And that was really significant to me. I one book I read was “Reclaiming Conversation” by Sherry Turkle, and she has a passage in there about the idea of the term cookies that we when we go to a website, we are invited. We are asked if we want a cookie, and that cookie sounds so benign. But actually the cookies are a way of being tracked to some extent.

Krys Boyd [00:06:39] Yeah, they’re unsettling for people like May, who is old enough to remember life without them. What’s so interesting, though, is that her kids are not only not fazed. They love these things. And it made me think about the fact that you are a member in your early 40s of probably the last American generation ever to live through childhood without, say, smartphones or computers all the time, raising one of the first generations to have never existed in a world without them.

Helen Phillips [00:07:09] Yes, it’s a strange position to be in. When I was in college, there was no social media. And then immediately after there was. And I think that is a bright line for people’s experiences. And I do think a lot about this as a parent. And we parents have to make difficult decisions all the time about how much screen time, when to introduce screen time. And these technologies are so enticing and are designed to be so enticing that it can be really challenging to navigate as a parent. And even the surgeon general of the United States has recently said some very compassionate things about this issue. And at one point in the book, Lou, the daughter says to her mother, I’m I can’t believe that you had to grow up without a bunny. The bunnies being the technologies that the children wear permanently on their wrists. And a lot of issues in the book arise from May deciding to remove her children’s bunnies. But her daughter says, I feel sad that you didn’t have one when you were a child. So as though the child has some relationship with the technology that the mother can’t even comprehend.

Krys Boyd [00:08:18] And what’s so interesting is the parallel is that May feels sad that her children have only known life with these bunnies on their wrist.

Helen Phillips [00:08:27] Yes. May believed in her own way of being raised. And the children believe in their own way of being raised. And maybe there is something there about the incredible adaptability to different situations. The technologies in the book are very distressing to May because they’re new to her. But her children, for her children, they’re simply the water that they swim in, in the air that they breathe.

Krys Boyd [00:08:52] In the story, you also raise this vexing question of whether the hums programed humanlike qualities make them eligible in any way for like rights or even empathy. Would you describe the scene early in the book where May is in a self-driving taxi called a V and the vehicle sort of unapologetically runs over one of these hums?

Helen Phillips [00:09:14] So, yes, that scene was one of the earliest that came to me in the writing process of the book. And May is in this self-driving vehicle which hits a hum in order to prevent her from being harmed in an accident. So there’s an obvious prioritization of human well-being over hum well-being. But when May is looking in the rearview mirror and seeing the hums body lying in the intersection, she’s very perturbed by it. And this complexity of her relationship with the harms really endures throughout the book. And by the end of the book, I think that her sense of the hums selfhood has really shifted.

Krys Boyd [00:09:59] I mean, we know and May knows that this is ultimately a robot hitting a robot. But in this initial scene, the fact that she’s still disturbed points to the anxiety that the hums feel similar enough to conscious beings, maybe even similar enough to souls, that it bothers her to see one destroyed and left like garbage in the street. And it made me think about this moment. I mean, my mom talks to her Amazon device with the same politeness she would use to a human in the room.

Helen Phillips [00:10:31] Yes. One thing that came up across a lot of research I did about artificial intelligence is the ease with which we can we as humans can attribute human emotions to AI and can also experience what feels like empathy coming out of AI towards us. We’re very wired to if something has eyes, for instance, that can kind of look at us, to feel like that really is another human or another entity that cares for us. So this really, I think, does complicate human AI relationships our desire to believe in the selfhood of these entities.

Krys Boyd [00:11:14] So this hum that gets run over is run over so that the self-driving taxi that May is in you know, won’t cause injury to her which takes us up against Isaac Asimov’s three rule of robotics, the first and primary of which is that robots cannot harm a human or allow a human to come to harm. Of course, there are lots of ways robots might enhance and simultaneously diminish human well-being. Right? Like it’s great that a hum can’t kill you, but if it renders you unemployable, that is still harm.

Helen Phillips [00:11:45] Yes, those rules were very interesting to me when I was writing, and I did think about them. But of course, you are right. It often situations are more complicated and assessing harms is not necessarily a straightforward thing.

Krys Boyd [00:12:01] And we don’t really know except in the most distant way. Who are the humans that are in charge? We now have robots sort of doing the dirty work so that whoever is making decisions is very distant in this book.

Helen Phillips [00:12:17] Yes. And I certainly I thought of that when I was writing, but I didn’t do a deep dive in the book into the system that has put these homes out on the streets. There’s just the sense that there’s a mention of a company that has figured out how to so elegantly embody the expansive brain of the network and has given them physical form.

Krys Boyd [00:12:41] So May is out of work. Her husband, Jim, is signed up for something like TaskRabbit, which is this gig job service performing the last remaining handful of things that humans are better at than machines. But thinking about Jim’s unrewarding work made me realize that being assigned by a computer to go all over town doing these jobs might feel to the worker a lot like being a machine.

Helen Phillips [00:13:06] Yes. And I think that you see in Jim’s character the strain of that. And at one point, he even says it would be too expensive to pay a hum to do what I do. So there’s been a real devaluing of his work. The most significant outcome or the most significant hope that he finds is that he and Mae are able to reconnect at the end of the book in a way that has been very elusive for them. But in terms of his work, it’s a very challenging situation that makes him feel undervalued.

Krys Boyd [00:13:39] Helen living in a big city, maybe living anywhere in this novel means that May and Jim and their kids are under constant surveillance. How does this create an opportunity for Mae to earn a small windfall that might keep her family going for a while?

Helen Phillips [00:13:55] Well, she finds out through a friend about a company that is doing an experiment where they’re modifying people’s faces so they can be recognized by surveillance. And they’re paying people quite a lot to do this. And because she has been displaced in her job by the artificial intelligence that she trained, she jumped at the opportunity to earn money this way. Of course, she doesn’t have to undergo a procedure, which is the first scene of the book where her face is being very subtly modified. There are 68 points to our face print, and if you modify some of those, then surveillance will have trouble recognizing you. And I did a lot of research when I was writing the book about adversarial technology and ways that people can modify their appearance to evade surveillance. However. Surveillance systems can also learn from these kind of technologies and actually become even better at detecting people. So May comes to understand that the experiment she’s participating in isn’t quite what she thought it was.

Krys Boyd [00:15:00] I thought you made a really interesting choice to start the book as may as having this procedure that somehow tweaks her features. Did you ever consider including scenes of her and Jim deciding she would in fact pursue this? I mean, it’s a really interesting kind of in media rather than you could have written a whole novel about the choice to essentially disfigure herself to make money.

Helen Phillips [00:15:24] Yes, that’s true. Well, the first thing that came to me of the book that came to me very early on is this first line. The needle inched closer to her eye and she tried not to flinch. And that was that line. Even with the slight rhyme of inch and flinch, I knew that that would be the beginning of the book. When I get the first line that I know that I have, the start, that I have the book ahead of me. And I like to begin in medius race. I like to throw people right in, especially in a world building situation. I think putting the reader concretely in an intense moment is a good way to draw them in. And then some of her decision making process is occurs in flashback in that scene. But another response to that question is that when I was 11 years old, I lost my hair due to the autoimmune condition alopecia. And when I was about 13, my mother and I made the decision that I would have my eyebrows tattooed onto my face because I had lost all of the hair on my face. And the experience of at that age, receiving those tattoos was very memorable and intense. So the sense memory of that is also part of that scene. Aside from the plot and thematic elements.

Krys Boyd [00:16:45] Were you thinking at the time about the fact that those tattoos, presumably they were something you wanted, but it was also something you couldn’t get rid of, like they would effectively be with you for the rest of your life.

Helen Phillips [00:16:58] Yes. And they’re still there and I’m very fond of them. They certainly feel like part of my body. I don’t regret having them, but it was intense to get tattooed so close to your eyes. And so I guess I’d say I’m grateful to have the tattoos and I’m grateful that that intense experience inspired the first scene.

Krys Boyd [00:17:18] So I just came back recently from an overseas trip, and I did not even have to pull out my passport on reentry. I just stood in for in front of one of those cameras that verify your identity. It is convenient. It speeds the process along. But with this book and so much surveillance made me realize we just rarely stop to think about other potential implications of having this technology in the world, especially in places in the world like China.

Helen Phillips [00:17:44] Yes, I did do a lot of reading about that. I have been very moved and intrigued by Cashmere Hill at The New York Times reporting on these issues of surveillance. And I think the book really is an exploration, both of the benefits and then the huge downsides that can come with being recognized. There is a point in the book where May is absolutely desperate to be recognized by a hum in order to be reunited with her children. And I’ll try to avoid spoilers. I’ll just say that. And then there are times in the book when the fact that she is as recognizable as she is causes a lot of problems for her there. The epigraph to the book is from Paracelsus, the Physician and Alchemist from the 1400s,”Poison is in everything and no thing is without poison. The dosage makes it either a poison or a remedy.” And that phrase he certainly was writing long time ago, not writing about technology. But for me, that really captures it. The dosage makes it either a poison or a remedy. It just depends on how we use these essentially miraculous technologies at our disposal.

Krys Boyd [00:18:59] It wouldn’t seem possible to even dream up devices that are more isolating than our individual phones and tablets screens, especially if we have headphones on. But you managed to do it here. Talk about these egg shaped pods known as wooms spelling “woom.”

Helen Phillips [00:19:17] Yes. So the wounds are, as you say, these egg shaped pods that every individual owns. And they are high technology, high tech, you could say, but they are subsidized by advertisers. So you can enter these egg shaped capsules, essentially pull them down over yourself and stream whatever you want on the Internet. The only catch is that if you get the cheap version, you’ll be advertised to in this very immersive way every eight minutes or so. And you could say on the one hand that that is a very futuristic element of the book, but I basically don’t see it as much of an exaggeration of the way that we all fall into our phones already and separate ourselves from one another by way of our phones.

Krys Boyd [00:20:06] There is so much in this book about maternal anxiety, this sense that we are trying to figure out the right way to parent in a world for which we have no or very few examples to draw on from our own childhoods. May and Jim as parents, both care deeply about their kids, but she worries about these things, it seems, in a fundamentally deeper way. Is that her character or is that something about women and about motherhood?

Helen Phillips [00:20:34] Well, I think part of that is because since the book is a close third point of view with May, we just know a lot more about what she’s thinking. And we live more deeply with her anxiety than with Jim’s. So I do think that we just don’t know as much what what is going on with him. What I do think, and this is also true as I share the book with the world and go on book tour, some of these anxieties and even the way that may as a mother, get shamed at one point in the book. Does feel very much related to motherhood and to the pressures that mothers can sometimes feel to be so strong, so loving, so stable. In a world where those things can be really hard to achieve all the time.

Krys Boyd [00:21:24] The book also made me think about the fact that in the society we inhabit right now. Part of proving to oneself that you are doing the best job you can as a parent is constantly thinking you’re getting it wrong. Like the mothers we eye with the most suspicion are the ones who seem to not constantly be second guessing themselves, whatever their choices are.

Helen Phillips [00:21:46] Well, yes, certainly we see May throughout the book trying to do the right thing. Stumbling, Doing the wrong thing, even when she’s acting with her best intention. And for better or worse, I do think that that is how motherhood can sometimes feel.

Krys Boyd [00:22:05] So the family needs the money that she earns from her procedure for basic necessities. But I have to say, it was easy to empathize with her desire just this once to use a chunk of it, to just give her kids an amazing experience. Like in some context, you might judge that, but if you’ve ever like been strapped when your kids wanted something, you can understand how powerful that drive is.

Helen Phillips [00:22:32] Yes, it is a poor financial decision, but she feels like it’s a really wise emotional decision to give her children who she fears are just not having the childhood, that she had to give them some access to that. So I appreciate that you feel empathy for that decision she makes because a lot of by a lot of measures, it’s not a very good decision.

Krys Boyd [00:22:58] The world is literally burning around them. Like part of the reason her kids can’t experience the same things she did as a kid is that the forest she grew up wandering has has burned to the ground. But consumer culture in May’s world is even more oppressive than ours, and nobody, even her seems to think about the ways those two things are connected because it’s like all they can do to say no to the pressure to spend money 50 times a day.

Helen Phillips [00:23:26] Yes. And that’s one treat that the hums have that we haven’t discussed is that they are constantly advertising to May. So she’ll be engaged in what seems like a deep conversation with the hum, and then it will break to say you really should buy new earrings or your your pants don’t look good. Here’s some other options. So there’s just this ubiquity of advertising and consumerism in her face unavoidable. And and also contributing to that feeling of guilt. If you bought this, then you would be providing better for your family. And she’s really under that pressure. And then at the same time, there are the fires burning in the sense of the environment facing a lot of degradation. And actually the one in the book who says this, who makes this connection most insightfully is the hum. Towards the end, she pays a lot of money to turn off the advertising so that she and the hum can engage in a deeper dialog. And the Hum says a very insightful line that actually came from an interview I did with my colleague at Brooklyn College, Ken Gould, who’s a sociologist that connects the degradation of our landscape to our desire to buy lots of things, and I’ll let you read the book to find that line. But it’s a great line that Ken said.

Krys Boyd [00:24:44] The scenes at this urban oasis known as the Botanical Garden, which is where May takes the family, were so poignant for me. I mean, it’s all kind of artificially grown and literally reserved only for the very lucky people who can pay for it. But once inside, even knowing it’s not 100% genuine, they do have a handful of magical moments.

Helen Phillips [00:25:08] Yes, I really wanted to give this family that gift. They’re having a hard time and it was really fun to write those scenes. One early inspiration for the book was thinking about the residents of green spaces. When you live in an urban setting like I do. So for me here in New York, Prospect Park and Greenwood Cemetery are some of the large green spaces near me. And there really is truly almost a magical feeling to entering a green space when you have a lot of concrete around you. And I wanted to really try to capture that on the page and just to capture their delight and connection to a green space.

Krys Boyd [00:25:54] You do such a masterful job of helping us understand just how unusual this experience is for them in the garden. Liu, the daughter, is alarmed by eating a tomato plucked off a vine because she worries it could be poisonous. She has like no experience with anything like this.

Helen Phillips [00:26:14] Yes, there is a certain awkwardness that the children have there in this very beautiful natural setting. And yet they especially, Lou, the older child, it takes her some time to adjust because she just hasn’t had exposure to that. And I do think that. Some relationship to nature is very important for people to have.

Krys Boyd [00:26:40] I also found the scenes there where there in the little cottage that they rent, you know, and they have these very artfully presented meals and there’s like, you know, jam on the table with the sunlight streaming through it and cheese wrapped in a cloth or whatever. Boy, that felt like someone’s Instagram feed. Some, you know, mom influencers, photographs.

Helen Phillips [00:27:02] Yes. And indeed, a lot of the reason that May want to go to the garden is because she had been seeing so much of it on social media. And she really is this desire that she has that feels very internal and personal, is very much inspired by the fact that she’s quite envious of what she’s seen. And I think that is a big motivator for a lot of people nowadays.

Krys Boyd [00:27:26] Lou has some pretty significant anxieties about being outdoors when the air quality is bad, which she’s constantly monitoring on this wrist device, her bunny. And I thought about how many kids today are sort of existentially stressed about climate change because they cannot escape those messages, but they don’t yet have any real power to do anything about it. And I thought you you really tapped into the fact that young kids can still have very big ideas about real things.

Helen Phillips [00:27:58] Yes, The anxiety about the air quality was present in the beginning and I’ll admit was somewhat inspired by one of my own children who who has who has shared that anxiety with me. And then after I had finished writing the book, there were a lot of wildfires burning in Canada and in New York City. We had really bad air quality. I believe it was in the June, June of 2023. And it was strange to feel that something I had written in the book when I was writing the future really had come to pass and quite a dramatic and striking way in a way that there was no hiding that from children. The sky was dark and it smelled like smoke. And you can’t there’s no hiding that.

Krys Boyd [00:28:41] Yeah. My son lives in Brooklyn and sent photographs and the sky was orange and other worldly. And what was so alarming was how relatively far away these fires were. But the impact was felt all over.

Helen Phillips [00:28:57] It was very, very dramatic and very alarming. And both of my children were very upset by it.

Krys Boyd [00:29:07] How do you how do you comfort them when you can’t say, it’s nothing to worry about because it is something to worry about?

Helen Phillips [00:29:15] That’s a really good question. You know, you bring them home, you turn on an air purifier, You you say it won’t last forever. And but it’s very hard. It’s something that makes parenting hard right now in this time. And and that was part of the impetus for writing the book. Just thinking what what will the air quality be like for them? What will and for children all over the world and what will happen to children all over the world as the oceans rise? I, I don’t know what to say to that. It’s hard to comfort our children. We need to get it together and try to do more concrete things so that we can say to them, Look, this is what we’re doing.

Krys Boyd [00:29:56] Helen I have to say, the scenes in the botanical garden made me realize and think deeply about how lucky we still are to be able to access nature, to have clean water and fresh food. But they were this reminder of the fact that taking this for granted puts it at risk. In this era of climate change, we can’t simply enjoy it anymore. We have to enjoy it and then do something to save it.

Helen Phillips [00:30:23] Yes. And if the book in any way makes people think along those lines that you’ve just stated. That would be my dream. And my reason for writing is to think we shouldn’t take this for granted. We need to celebrate the fact that we still have this, at least in many places, and we need to work really hard to ensure this future.

Krys Boyd [00:30:48] When there in this garden may feels some very familiar pressure to make every moment magical because she has dropped months of rent on this. And I thought about the fact that we’ve all felt that right, whether it’s, you know, the holidays or a birthday or, you know, a vacation somewhere, there’s this need to make sure you’re squeezing every dime of value out of it. And that’s not possible when you have, you know, a variety of human personalities and all there needs.

Helen Phillips [00:31:18] Yes. She’s under a lot of pressure and at the slightest rowdiness from her kids or discontent from her husband. She starts to feel like she has just been absolutely foolhardy to spend this money. So I don’t know if there’s a lesson there, but certainly that pressure characterizes her time there and at times even makes it hard for her to enjoy the experience.

Krys Boyd [00:31:41] So I will avoid spoiling the book, but I will just say that something goes wrong for the family while they’re in the botanical garden. And the person who gets the blame for this is, of course, May the mother. She finds herself the target of scorn because of this choice she made. Can you tell us as much as you feel like telling us so that we can sort of discuss this part of the book?

Helen Phillips [00:32:07] So. She, in an attempt to help them really enjoy this experience of going into this garden that she’s paid so much money for. Request that her family leave their technological devices at home so that they can really be deeply engaged in this place. So that means for the children to move their so-called bunnies that they wear on their wrists for her husband and for her to leave their phones at home. And this is hard for her. She often tries to take a picture or look for directions and then realizes, I don’t have my phone. Almost like missing a limb. So it’s not easy to leave these things behind. But. But they do do it. But then something happens to the children and she is desperate for her devices and desperate for their devices and realizes in a very raw way how reliant they are on them. And I’m trying to not spoil the book. Okay. But then when it when it gets out more publicly, what she has done, she faces a lot of judgment for it.

Krys Boyd [00:33:14] It made me think about how hard some of my friends are finding it to turn off or resist like life 360 type monitoring software. Even as their kids grow up and head off to college or become young adults because these things that didn’t even exist 15 years ago now feel like like the baseline of security because we can have them. We feel like we must have them.

Helen Phillips [00:33:40] They’re very powerful. They do contribute to a feeling of safety and control for your loved ones. And on a personal level, I write as I was finishing up the book, my daughter, who was in fifth grade, wanted to start to walk to and from school alone, and we had to figure out what the situation would be that would enable that because I was glad that she was wanting more independence, but also trying to balance that with my parental concern. And we did end up getting her a watch that we could use to communicate with her and see her as she journeyed alone, which was, of course, very comforting. But I could not help laughing with the sheer irony that I was just writing this book about the children’s addiction to their devices and then getting my own child this kind of device. And I. I feel like the system makes hypocrites of of certainly of me and maybe of all of us.

Krys Boyd [00:34:38] Yeah. And I also appreciated the fact that you, you know, you have May sometimes just missing her device for the distraction it provides. So like that’s all of us, right? We might realize we’re on our phones too much, but if we happen to go somewhere and we we’ve left it on the kitchen counter we like May don’t feel complete. We don’t know what to do with ourselves if we’re waiting in line or, you know, not fully occupied.

Helen Phillips [00:35:05] We are deeply entwined with them. So deeply entwined. And it’s certainly understandable. And certainly these apps are well designed to give us that sensation and it’s understandable. Our phones are incredibly useful and give us access to so much. But as I mention the epigraph of the book, what is the amount that makes it a remedy and not a poison? I think walking that line, that line is very hard to find. I’m always seeking it.

Krys Boyd [00:35:40] I also read your last novel, The Need, and I have to say I would have known you were a person with children, even if I knew nothing about your biography, for one thing. You write kids smarts in a recognizable way as like people with real and distinct personalities. But you’re also so keyed into the way that they often see the world in absolutes.

Helen Phillips [00:36:03] Yes, I do credit my children with being very helpful research as I as I write about motherhood and try to explore motherhood. And indeed, that theme interests me because the experience of being a mother is so much more complex, interesting, dazzling and challenging than anyone could have ever prepared me for. But in terms of evoking the children’s characters, I am really struck by or one thing that surprised me about having children is how even at such a young age they have so much dimensionality and personality. They really are full human beings, even when they’re really young. And I have strived both in Hum and The Need to try to create children characters who really have that depth of personality.

Krys Boyd [00:36:59] The other thing that’s surprising. I’ve gotten used to it now because I’ve been a mother for a long time, but from a very early age. They join the wide circle of people ready to criticize your mothering.

Helen Phillips [00:37:13] Indeed. They’re the real experts on that. I remember when my daughter had just learned to read and I bought some parenting book and she was reading the parenting book and it was about conflict or something. And then I was navigating a conflict between her and her brother, and she said, Mom, you’re not doing it right. That’s not what the book said. So she got me.

Krys Boyd [00:37:37] In the need to play with the idea that it is impossible for like, one human woman to be everything that is required of a mother and a spouse.

Helen Phillips [00:37:50] Yes. And really, the premise of the book is based on that idea, the challenges of of trying to do it all.

Krys Boyd [00:38:01] In both these books. What’s interesting is that these struggling mothers struggling because the world is hard, not because there’s anything inherently wrong with them. They both have partners who love them, and yet they feel very much on their own with the pressures of motherhood. Like even when we have a partner who by all accounts is supportive and a good parent. It seems like there are some agonies of motherhood specifically that nobody can quite relate to outside of that role.

Helen Phillips [00:38:30] Yes, I do think that both of the books that’s definitely true of both of the books. Again, we are in close third with the women, so we don’t know what their partners perspectives are. But I think that even when you see what happens to May in Hum and the way she gets treated by the broader world, that is a manifestation of the really intense expectations that are put on mothers to to be a lot of things for their families.

Krys Boyd [00:39:06] Does most of the work happen for you in the research beforehand? Are you like an inveterate rewriter? Like how is your process? How does it work when you’re refining what a story will be?

Helen Phillips [00:39:20] Well, I do begin with doing a lot of research, and I, I start a book with a 100 page list of images, plot ideas, research over heard lines of dialogue. And then I use all of that into a roughly laid out plot. And then I write a draft that I call Draft Zero, and it’s a big baggy draft and I call it draft zero, so that I’m not putting too much pressure on myself. And then after I have Draft zero, then I write the what I consider the first draft where I really begin to give it more shape. Though the research is important. I actually end up usually taking out a lot of the research oriented passages because it doesn’t make for a good story. So it’s really an interweaving. The research is important but also can’t overshadow the human story.

Krys Boyd [00:40:15] In The Need, your protagonist is someone who very much enjoys her work and feels called by it and also has responsibilities at home and very much wants to be with her kids. And I wonder, I mean, writing requires such extraordinary focus. What does it take to feel you deserve that time when your children are very small because otherwise your work won’t happen?

Helen Phillips [00:40:42] Yes. Well, I think that I’m in the lucky position that. I since I was six years old. I knew I wanted to be a writer. And when I lost my hair, as I mentioned before, writing was really comforting to me and it was a way of processing it. And I also grew up with a severely handicapped sister. And writing was a place that I explored that challenge, too. So writing for me is a place that I turn to with all sorts of emotions. And so even though maybe logistically it’s harder to find the time to write, as a parent, I feel like the more complicated my life is, the more necessary it is. So even if it’s just an hour or 30 minutes a day, I really try to fit it in because it’s important for balance.

Krys Boyd [00:41:36] Is there something about that experience? I believe that you don’t choose to wear a wig or a hat most of the time in public appearances. Is there something about that experience of of being conspicuous because most women in our culture have hair or wear hair that that steals you for people critiquing your work in a way that may not be fully informed.

Helen Phillips [00:42:03] That’s a really interesting and actually really beautiful question. So when I lost my hair at age 11, it was a really painful experience and a difficult thing to have in early adolescence. And for many years I wore wigs. And then for many years I wore scarves. And I felt very self-conscious to be a bald woman in our society where hair is really associated with beauty a lot of the time. And then this the exact same week that I published my first book, which is a collection of very short stories called And Yet They Were Happy. I realized, why am I still covering my head? I am so exposed in my writing that to continue to cover myself in this other way just seems unnecessary now. And it was so liberating to just say, okay, I have exposed my emotions in my writing. I have exposed my inner thoughts and now I shall expose my head. And I will tell you that though it took me bracing myself on the streets of New York, a bald woman is never the oddest thing that anyone has seen on a given day. So I did not feel, despite my concern, I actually felt very embraced by the world. It has been a very positive experience, though I dreaded it for the first, I guess, almost 20 years of being bald.

Krys Boyd [00:43:22] I’m really glad to hear that, because I imagine in the beginning when you make the choice, even if you think it’s the right choice for you, maybe you don’t for a while even want people’s lovely compliments about how striking you look.

Helen Phillips [00:43:34] Well, I’ll take the compliment at this point in my life, certainly. But it. Yeah, it is certainly, as you say, you when you look at different like this, it does make it more likely for people to make comments to you. Or I’ll have things where people ask, how is my cancer treatment going? And then I’ll explain to them that I have alopecia. But usually the person is asking because they’ve gone through that or they have a loved one going through that. So truly looking this way has opened up a lot of conversations for me that I never would have had otherwise. And particularly as a writer, I’m always interested in talking to people.

Krys Boyd [00:44:16] Collecting stories as you go along.

Helen Phillips [00:44:18] Collecting stories. Indeed, yes.

Krys Boyd [00:44:21] Author Helen Phillips is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers Award. Her new novel is called Hum. Helen, it’s been a real pleasure. Thank you for making time for the conversation.

Helen Phillips [00:44:33] Of course. Thank you so much for your questions. I really appreciate them.

Krys Boyd [00:44:36] Think is distributed by PRX, the public radio exchange. You can find us on Facebook and Instagram and anywhere you like to get podcasts. Just search for KERA Think and you’ll find our show. Our website is think.kera.org and when you go there you can learn about upcoming shows we’re planning and also sign up for our weekly newsletter. Again, I’m Krys Boyd. Thanks for listening. Have a great day.