As the 2024 election approaches, plenty of voters are asking why isn’t there a third option? Jeffrey Engel, Director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University, joins host Krys Boyd to discuss the history of third-party candidates, from Teddy Roosevelt to Ross Perot, and how they’ve impacted – or not – presidential elections.

The U.S. political landscape doesn’t leave room for a third party

By Shaunessy Renker, Think intern

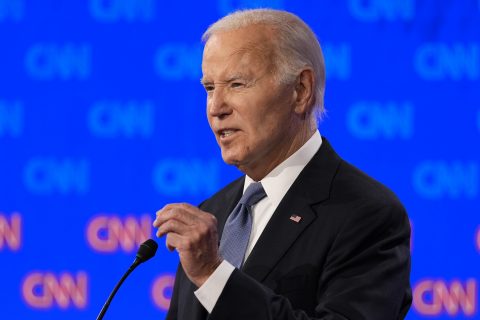

We seem to be in an age of polarization when it comes to U.S. politics and many Americans feel dissatisfied with the candidates our bipartisan system has to offer this election year. According to a poll conducted by Gallup, 29% of Americans said that neither Trump nor Biden would be a good president. With more voters feeling like their views aren’t represented by either party, it seems that now would be the perfect time for a third party to swoop in and throw the election season off its course.

There have been third-party candidates who’ve shaped election outcomes before, but none made it to the White House so far. Jeffrey Engel, Director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University, explains why.

Engel says one of the reasons a third party hasn’t won is because they lack legacy and branding. Though they have evolved, both parties had years of establishing their logos, campaign slogans, merchandise—something a third party starting fresh wouldn’t be able to keep up with.

“You are more likely as an American to switch religions than you are to switch political parties,” he says. “Our party affiliation has become our most significant identifier of who we are as a person in this country.”

Another significant reason Engel gives is the amount of money running for president requires. He says that in an era of unlimited funding for candidates, big donors do not want to place a bet on someone who has low chances of winning because they want to gain something from their investment.

This election year, it seems there won’t be a significant third-party candidate who will challenge both Trump and Biden for the White House. In states that allow the Democratic primaries, there was a considerable increase in voters who cast a ballot for “uncommitted.” For example, according to the Connecticut Secretary of the State’s Office, 11.6% of votes in CT Democratic primary were ‘uncommitted,’ more than the previous two presidential election years combined.

“What they’re [uncommitted voters] basically doing is helping the person they like least,” says Engel. “I pray that the people who are upset and have vocalized their dissent with the President and with Trump wind up essentially remembering that they have a civic responsibility to cast a ballot, not just to stay home.”

In contrast to voters who are uncommitted, there are Democrats and Republicans who vote for their party’s candidate even though they may not like them.

“That’s a little scary because that means that essentially you’re deciding that what unifies you is less important than what divides you,” says Engel. “You’re no longer an American. You’re a Democrat or a Republican, you’re red or blue… that tells you your party affiliation is really powerful. That’s not a good recipe for national success.”